On the second anniversary of the Zapatista uprising, January 1, 1996, the EZLN published the Fourth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle as a call to reorganize the social movements standing in solidarity with the Zapatistas into a new political (but not electoral) organization. Concurrently, the First Declaration of La Realidad Against Neoliberalism and for Humanity was published on the same day. The latter document also announced a worldwide gathering in late July, with preparatory meetings in each continent in early April.

La Realidad, a small community of less than a thousand people in the canyonlands of the jungle in the municipality of Las Margaritas, Chiapas, was the place hosting the April gathering for the Americas. Shortly after, the EZLN appointed an Organizing Committee of half a dozen personalities, including actress Ofelia Medina, activist Flora Guerrero, and other names I can’t recall. I don’t remember if my friend Rebeca Y., an archeologist by profession with the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), was initially appointed a member of the Committee or if she just happened to be the efficient ally that ended up volunteering. The truth is that most of the personalities in the organizing committee had little time on their hands and, frankly, even less desire to deal with the minutia of the logistics for such an event. I was a graveyard shift lab tech with no need for sleep, so I plunged in. By mid-February, we were holding regular meetings and expanding our logistics team. For some reason, Rebecas’s team (my team) got stuck with the task of credentialing attendees.

In early March, the EZLN issued the official invitation and a preliminary list of invitees, and oh boy, it was studded. It included actors Kevin Costner and Jodi Foster, singers Silvio Rodriguez and Mercedes Sosa, and others. Naturally, it is not like Sub Comandante Marcos had a Rolodex with all those contacts for us to copy and start faxing or calling. Fortunately, the EZLN had an official representative in the US named Cecilia Rodriguez, and the Hollywood celebrities became her problem. We only had to deal with rejection from Latin American celebrities. Somehow, we must have spoken a different kind of Spanish to Mercedes Sosa, who sent back a request for USD 5,000 to make an appearance, or it could be that the person who reached out to her did it through her agent and that is just how agents respond.

Not all celebrities rejected the overtures. If something characterized the EZLN’s movement was the status of celebrity Sub Comandante Marcos achieved and the constant parading of celebrities through the Chiapas’ jungle. During the La Realidad gathering, Edward James Olmos attended the breakout discussions. Still, the small village saw Danielle Mitterrand (widow of the late French president), Oliver Stone, Regis Debray, Manu Chao, and Zack de la Rocha during the weeks before and after the event, just among the names I can remember.

The logistics work was grueling, from sending invitations, designing and printing badges, setting up transportation and lodging logistics, keeping tabs on registrations to monitor capacity, etc. The task was gargantuan. A foreign invitee would have to arrive in Mexico City to find their way to San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, where we would arrange transportation in small (and very uncomfortable) buses through the rough dirt and muddy roads to the jungle. Once there, everyone would use their sleeping bag to spend the night, and hopefully, a hammock, if they packed one, would save them from the critters that crawled the floors. The community had set up latrines and improvised showers.

Many of us, loyal followers of Rebeca, had spent weeks preparing this. But when we arrived at La Realidad, we got confined away from the main groups, restricted in our movements, but still with a lot more tasks to perform. It was in that context that some of us started to get cranky. We didn’t appreciate the treatment from the EZLN and other participants. We were customer service for attendees, and management treated us that way. In one contentious situation, the press was furious at us for confining them to a bullpen. It was well known and evident that certain friendly reporters had unrestricted access to the village, the backstage, and the leaders of the EZLN. The nonfriendly Mexican press and the foreign correspondents were not happy getting restricted to the sandbox. At least once, a reporter got almost physical with one of my colleagues for denying his request to leave the conference area.

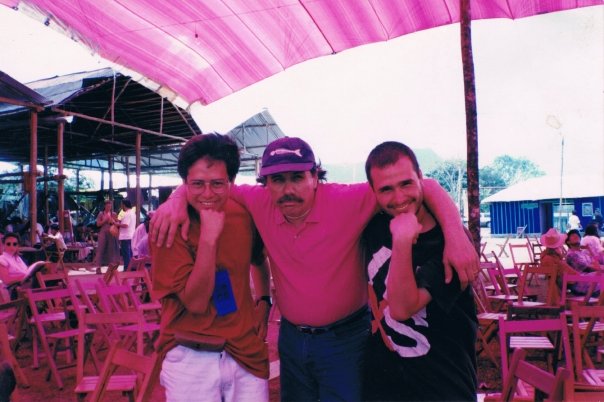

But most everyone was having a good time. And we got resentful. My friend Jacques N. and I had been poking fun at Comandante Tacho, whose celebrity status had him posing pensively on the cover of a few magazines. As soon as we got to move around, we found the first celebrity, which happened to be Edward James Olmos, and took our picture reproducing Tacho’s pose. The unsuspecting actor was just an accessory for a prank, not unlike the rest of his career, just for fun. He was just an outlet for our displeasure.

The last straw happened on one of the podium interventions by Marcos. He thanked the organizing work of many people who had not done anything. I can’t remember who started drafting the letter protesting our treatment, but we all signed it. I can’t remember what exactly it said, but we were pissed. We made it clear we were there with Rebeca and for Rebeca, who still had a job to finish.

On the closing night, Sub Comandante Marcos made a peace offering. Rebeca got to sit by him while he thanked again, albeit in more general terms, all those who helped organize the event. AP archive video shows a nervous Rebeca sitting up next to the gods, rubbing elbows thanks to our tantrum.

Leave a comment